The Dharamsala gathering highlighted the work of several teams of educational practitioners, who are expanding traditional notions of social and emotional learning (SEL) to incorporate the training of attentional and emotional skills, compassion and altruism, and systems thinking.

These teams, and their new programs, are building upon and extending the reach of SEL skills in ways that emphasize social and global awareness, ethics, and productive social engagement. These new curricula stress, not only a student’s relationship to self and others in their immediate environment, but their ethical engagement as citizens within a global community. Ultimately, they seek to cultivate understanding of the interdependence between personal and collective flourishing.

An Example of SEL 2.0 in the Classroom: ISEE

Presentations by teachers offered compelling examples of these cutting edge SEL programs, demonstrating to the Dalai Lama how his vision for educating the heart is becoming a reality. The program creators showed videos of children of all ages practicing SEL. In one clip, about a dozen five-year olds were sitting cross-legged in a half circle on the classroom floor. When the video begins, they are singing playfully, but then their teacher instructs them to do something out of the ordinary that many adults would find challenging. “We will take three deep breaths and see what is happening inside [ourselves],” the teacher prompted. “Is it hot? Is it cold? Is it tense? It might be easier if you close your eyes.”

This technique is called ‘taking your emotional temperature,’ classroom educators Sophie Langri and Tara Wilkie explained. As co-founders of the Institute of Social Emotional Education (ISEE), Langri and Wilkie have developed a SEL program based on secular ethics, which they have been teaching to children in elementary schools in Montreal, Canada since 2009.

Photo by Tenzin Choejor.

The children in the video were learning to identify three basic emotional states, which exist on a continuum. “High energy emotion would be like a volcano; I’m about to explode,” Langri explained. High energy feels angry, frustrated, or irritated; it could also feel excited or happy, she explained. “On the other side, you have the iceberg, which is low energy.” Low energy feels sad, tired, or sick, she said. “In the middle, you have the tree zone.” Tree zone is calm and alert. Children point to the image on a poster that corresponds to how they feel.

As the video continued, a timid girl with a pigtail who said she was ‘in the volcano’ took her turn at another poster, which Langri and Wilkie called a ‘feelings and needs’ chart. On the left side, the chart showed 15 faces displaying different emotions with the name of the emotion under each face. The girl smiled as she pointed to the face on the poster that matched how she felt: excited. “What do you think you need?” the teacher asked. The right side of the poster offered 15 suggestions. Again, the girl pointed to one: “Calmness.” In a subsequent video, older children chose emotions from a deck of 40 cards.

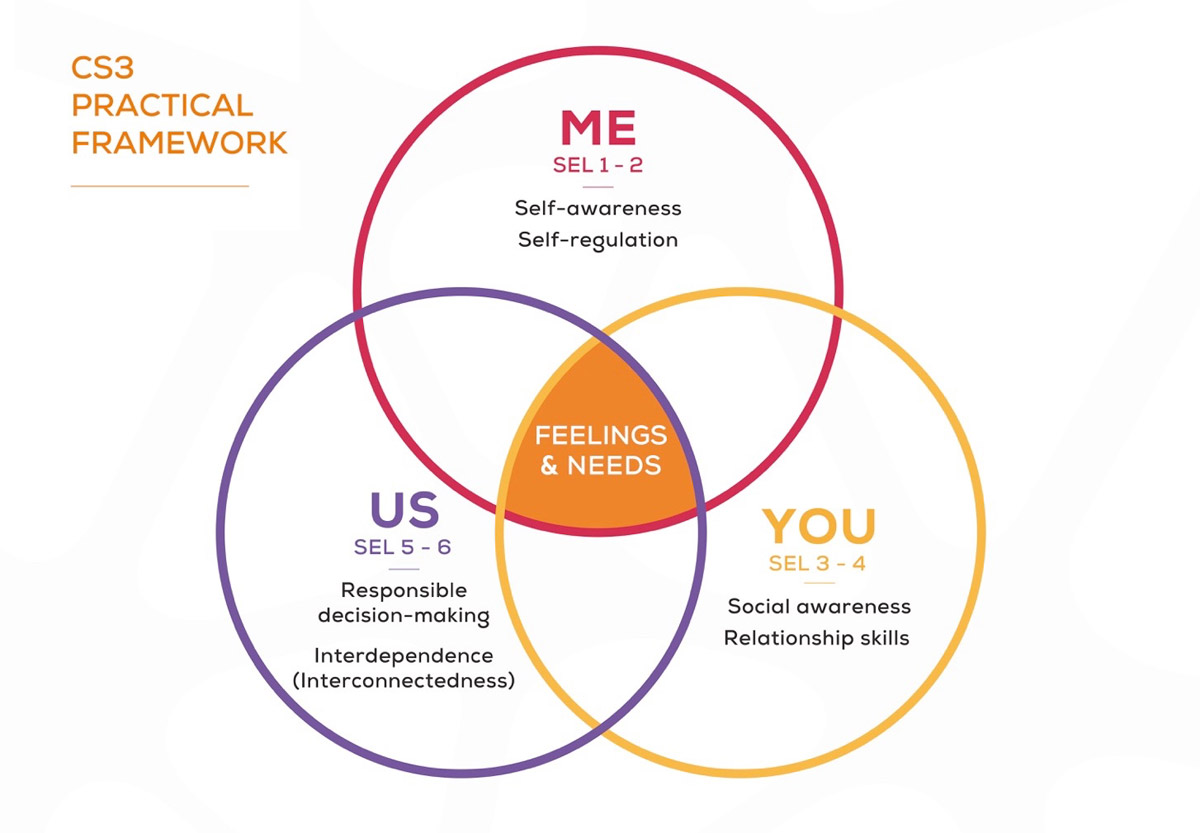

Me, You, Us

Wilkie explained that the ISEE’s learning framework encompasses standard components of SEL—self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making—but it includes one more element that Wilkie and Langri consider essential: interdependence. These components fall into three domains: Me, You, and Us, explained Wilkie. The ISEE framework reflects a growing understanding—as manifested in the global climate crisis—that we have to have personal, social, and collective responsibilities to others because our happiness and others’ happiness are interdependent.

The Me Domain creates the foundation for what Langri and Wilkie call “emotional literacy.” Relying on practices and supports such as the emotional thermometer and feelings and needs chart, students learn how to turn inward and check in with themselves. They notice their degree of emotional activation and see how emotions affect their behavior. Then they learn to recognize and name the emotions they discover. As students connect their feelings to their needs in this way, they calm down. If they need to soothe themselves more, they run around the gym, get a drink of water, breathe deeply, meditate, or take a walk.

"We truly believe this is a 21st century literacy." Sophie Langri

Once students are able to articulate what they feel and need, they progress to the You Domain, developing relationship skills and social awareness so that they can address their own needs skillfully while being sensitive to the needs of others as well. In the You Domain, they develop empathy and compassion as they learn how to take another person’s perspective. Students receive conflict resolution training and write gratitude notes (or disappointment notes) “to celebrate the good stuff and identify the not-so-easy stuff,” said Wilkie.

Then the students advance to the Us Domain, which is where the importance of interdependence comes in. “In the Us Domain, students build compassion and empathy for people within the systems they participate in: their families, classes, and schools,” Wilkie explained. At that point, they develop critical thinking skills; they mature ethically; and they learn to make responsible decisions. By means of cooperative learning and teamwork exercises, conducted over an entire school week devoted to kindness and compassion, they build a sense of shared humanity and come to understand that their actions have impact on the world around them.

As Langri and Wilkie completed their presentation, they thanked the Dalai Lama for his vision. “We are very grateful,” Langri said. “We truly believe this is a 21st century literacy.”

"The key is: I, you, us. Eventually I think seven billion human beings should develop a sense of us." The Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama replied, “The key thing is ‘I, you, us.’ Eventually I think seven billion human beings should develop [a] sense of us.”

This kind of training should be widely disseminated, he recommended, especially in conflict-ridden areas where children are under considerable stress and distress. Langri concurred, “In our experience over ten years, we’ve seen that children do not like conflict. When we give them the tools, they will fix the conflicts [in their own lives]… This is why it is important to start when they are very young.”

It’s not only about managing conflict constructively in our lives, added Langri, but being able to “have arguments and trying to understand each other—and keeping respect while we are discussing different viewpoints.” In this way, this innovative program was not only teaching skills for dealing with life’s adversities, and even solving conflicts, but also skills to create greater mutual understanding in ways that could prevent future conflicts from occurring. By including the collective we and interdependence as key concepts in the program, ISEE’s work seeks to expand the range of traditional SEL skills to relationships, our common humanity, and the level of human systems.

Another Example of SEL in the Classroom: SEE Learning

In another video, a group of adolescents spoke to the camera about what they had learned from SEL education in secondary school. One young woman stated “I am coming to learn that emotions aren’t something that just come out of nowhere and take control of you. We create them ourselves. And so we have the power to guide them.” A young man declared, “It’s not about, ‘I am never going to be angry.’ That is just unrealistic. It is about trying to make these emotions work for you.”

These students attend Woodward Academy in College Park, Georgia, explained education consultant Jennifer Knox, a teacher at the school. Woodward Academy is the largest private independent school in the continental US, she said. It has 2,700 students; 49 percent are students of color. Knox, an alumna of the school, is also a core member of the Social Emotional and Ethical Learning (SEE Learning) team at Emory University’s Center for Contemplative Science and Compassion-Based Ethics. (Woodward Academy is one of their partner organizations.)

Knox and a team centered at Emory have developed a new conceptual framework and curricula for K-12 and higher education based on the Dalai Lama’s books Ethics for a New Millennium and Beyond Religion. Their pioneering work, similar in some ways to the ISEE program described above, expands the traditional model of SEL training to include elements such as the development of attention, cultivation of compassion, appreciation of interdependence, and dialogues around ethics.

The Need for a Triple Focus

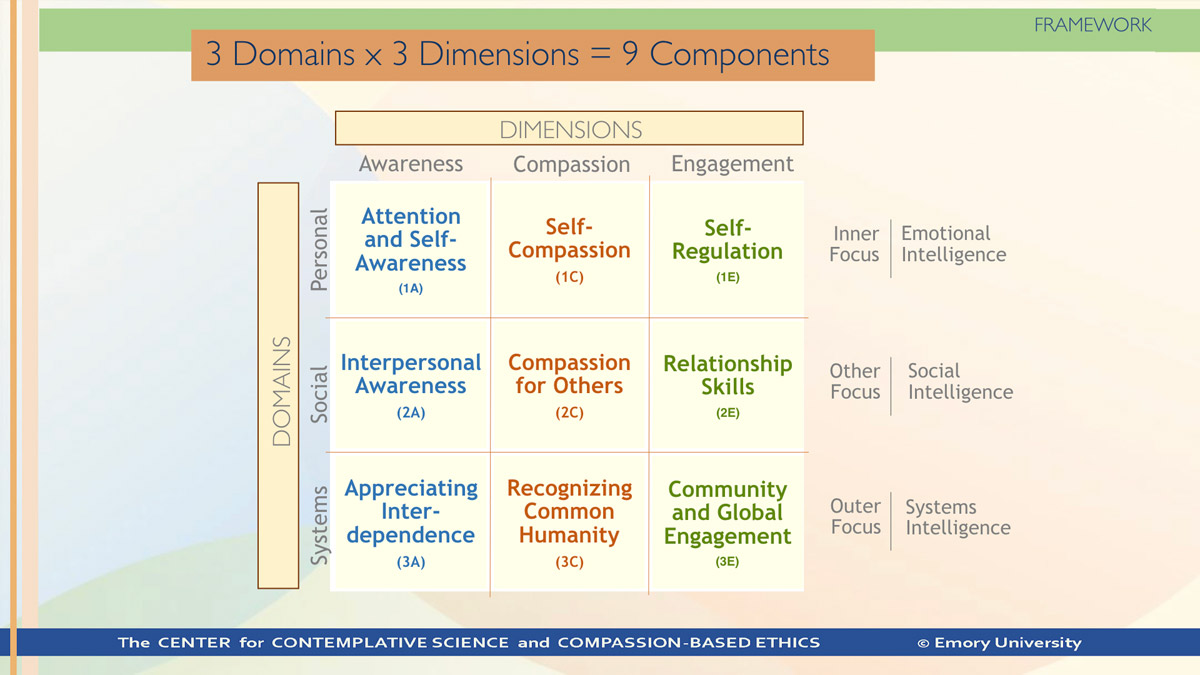

Central to SEE Learning, Knox explained, is the notion of ‘triple focus’ that conference co-presenter Daniel Goleman set forth with Peter Senge in Triple Focus: A New Approach to Education (2014). In that book, the authors identified three core skill sets they consider essential for today’s children, who are “growing up in a world facing unprecedented social and ecological challenges they will need to help address.” Each skill set requires a particular kind of focused attention. First, children need an ‘inner’ focus, which connects them with their most deeply held aspirations and sense of purpose. Second, they need an ‘other’ focus, and the ability to tune in to and empathize with other people and see things from their perspective. Third, they need to have an ‘outer’ focus and understand “the way systems interact and create webs of interdependence, whether this interaction is in a family, or an organization, or the world at large.”

Using this idea as a basis, the Emory group identified the social and emotional skills that are associated with the personal (inner), social (other), and systems (outer) domains. These skills were divided into three main categories: awareness, compassion, and engagement. Referring to the table (below), Knox showed how students build social and emotional skills sequentially by progressing from inner to other to outer focus, and from awareness to compassion to engagement across these levels. “When students build these skills through the three levels of understanding,” Knox said, “the ethical dimension is actually a spontaneous outcome.”

Image © Emory University.

As they were developing this framework, the researchers began to realize that not all students are prepared to start at square one. Developing attention and self-awareness requires turning inward and quieting the mind, but for children who have experienced trauma, the meditation exercise of focusing on their breath could be triggering. Before these individuals could learn to meditate, they needed to learn to regulate their nervous system. So the researchers added ‘pre-meditation skills’ to the curriculum. “We’ve built an entire chapter based on building skills of resilience,” said Knox. This kind of trauma-informed approach is critical in a new generation of SEL programs.

Creating a Culture of Compassion

The Emory researchers understand that children can only thrive if their environment is supportive, so they aim to create what Knox calls ‘a culture of compassion’ in the classroom. “Part of the work that we’re doing is understanding how to cultivate teachers who are asking the questions of themselves that we wish the children to ask,” explains Knox. “Without the teachers developing those skills to a point of intended embodiment, we feel it is not possible for the students to engage in that work alongside them. And students have a role to play as well. From the outset, students create agreements of how they want to be together; for example, they establish beforehand how they want to respond if one child hurts another’s feelings. These group agreements are a living document. “Students revisit them, and add to them, and remind one another,” said Knox, “and that becomes the guiding culture, co-created along with the teacher.”

"Part of the work that we’re doing is understanding how to cultivate teachers who are asking the questions of themselves that we wish the children to ask. Without the teachers developing those skills to a point of intended embodiment, we feel it is not possible for the students to engage in that work alongside them." Jennifer Knox

The Dalai Lama asked Knox whether the word ‘compassion’ in English conveys the idea that you can be benefit yourself from compassionate acts. Sometimes when [non-Buddhist] people talk about compassion, he pointed it out, it means, “Some kind of self-sacrifice—giving up oneself.” But the type of compassion he promotes is a different sort, he explained. Because humans are social animals, our own survival, happiness, and joy very much depend on others. Therefore, it is in our own best interest to show respect and love for others. “Ultimately you get much more benefit than just thinking ‘me, me, me.’”

If people can change how they see the world, they can in fact perceive everything around them as a source of joy, he continued. “We must develop a feeling of dearness to the entirety of sentient beings… For someone who really takes the idea of universal compassion seriously, then any sentient being that is deserving of compassion can never be an object deserving of our wrath, anger, or hatred. There cannot be such a thing as an enemy, because anyone who is deserving of compassion should be seen as a true friend.” To some in the audience, this degree of altruism might seem unobtainable, but the Dalai Lama insisted it is a realistic possibility. Through furthering this potential through education, the Dalai Lama argued, “we can achieve a happy world.”

To learn more about the SEL frameworks and curricula described here, visit the Resources section. In the next chapter “Helping Students and Teachers Manage Stress,” presenters elaborate on the importance of creating school environments that reflect SEL principles.