Just as important as creating quality curricula and tools for social and emotional learning (SEL) is ensuring that students are ready to learn and that teachers “walk their talk,” modeling the very skills and attributes that form the basis of SEL instruction. In this chapter, two leading researchers present practical tools for reducing stress among students and teachers.

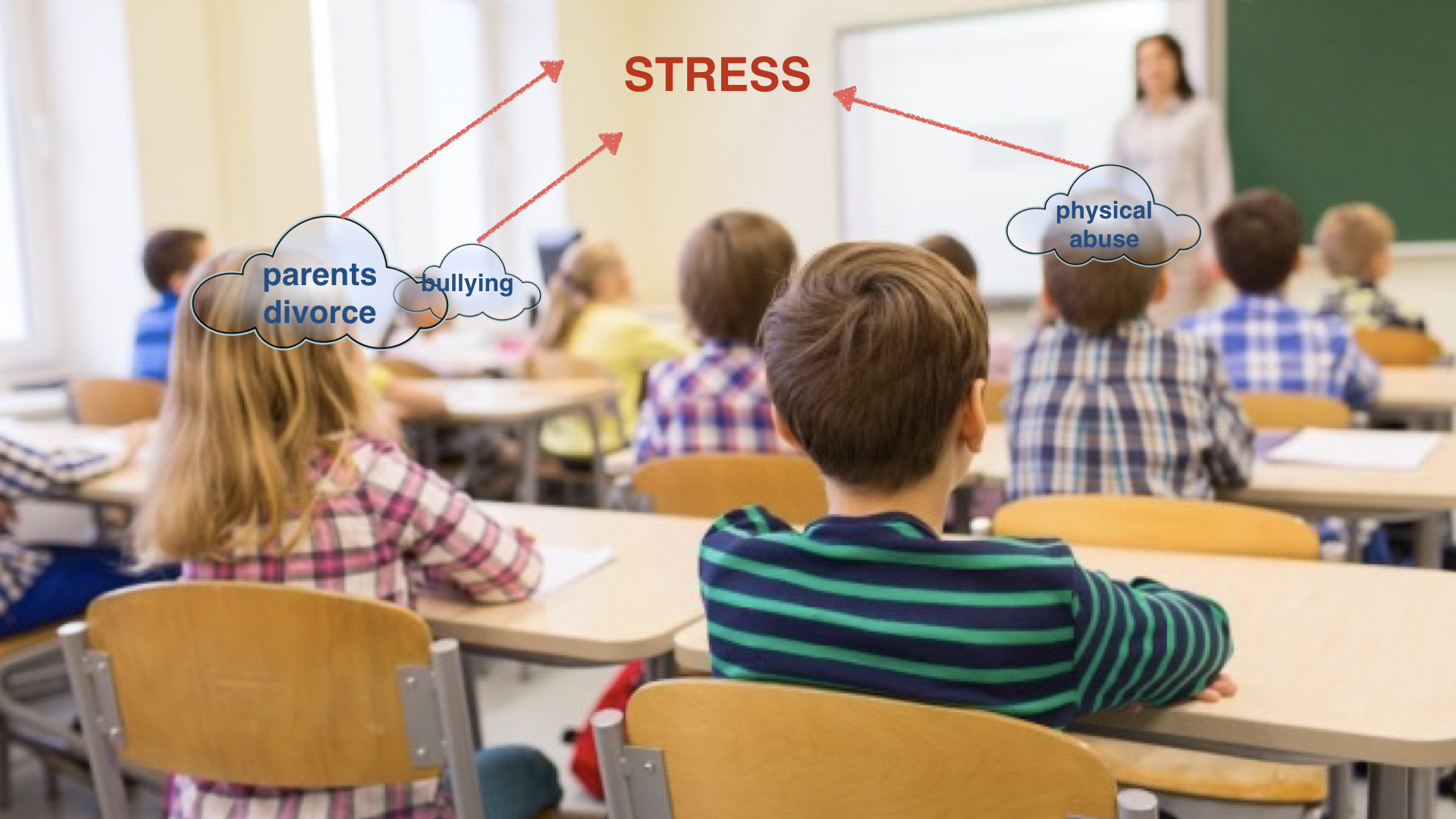

To illustrate the barriers that students enter the classroom with, Sonia Lupien, a stress researcher and Founder and Director of The Centre for Studies on Human Stress in Montreal, Canada, invited the Dalai Lama to play a game. “Let’s say that I am a teacher going into a classroom to teach SEL.” Lupien projected a PowerPoint slide showing a teacher in front of a classroom of children. Then she pointed to a boy sitting in the back row. “This child will learn,” she said. Successively she indicated three other children; they will also learn, she said. Then she pointed to a girl sitting in the back. In the PowerPoint image, a cloud appeared over the girl’s head. “This girl won’t be able to learn,” Lupien said. “Her parents are divorcing. They are in very important conflicts, and she doesn’t know what is going to happen.” Another cloud appeared, this time over a girl in the front. She wouldn’t be able to pay attention either. “For the last two weeks she has been bullied and she is scared.” And then a third cloud appeared over a boy in the front. “His sister is sick, and he doesn’t know what is going to happen to her.”

In this imagined classroom, teaching is happening; but for these children, learning is not.

Slide image © Sonia Lupien.

Reducing Student Stress: Destress for Success

The distracted students share a common affliction, Lupien said. “Stress.” Her research has shown that just as adults get wound up, so do children. Lupien differentiated between two kinds of stressful situations. Absolute stressors are situations that affect a child’s very survival, like war or extreme poverty. (“As early as age six, poor children have elevated levels of stress hormones,” she reported.) Relative stressors threaten not life but well-being. They are challenging and unpredictable situations over which one has little sense of control—like the parental divorce, bullying, or family member’s illness in Lupien’s example. Children are vulnerable to both kinds of stress, she said.

Stressed children don’t learn well. Through research conducted over 25 years, Lupien has discovered why. When someone detects a threat, Lupien explained, their brain produces stress hormones. Within ten minutes of secretion, the hormones have circulated through the body and return to the brain; and when they return, they target brain regions involved in learning, memory, and attention. “The first thing they affect is selective attention,” she said. Selective attention is the capacity to discriminate between relevant and irrelevant information, Lupien explained, and what is deemed relevant hinges on what is threatening. What was relevant to the distracted children in Lupien’s thought experiment was not the class lesson but threats experienced and anticipated: impending divorce, bullying, sickness. “If we want all these children to learn,” Lupien said, “it is going to be very important to first decrease the stress response in those who are suffering.”

"If we want all these children to learn, it is going to be very important to first decrease the stress response in those who are suffering." Sonia Lupien

With that motivation, Lupien started a program called Destress for Success. This program teaches children what stress is and how to recognize it, and also teaches them strategies for how to cope with and reduce it. Lupien teaches the program to teachers, who pass it on to the students in their classes. To date, Destress for Success has reached about 65,000 children. Lupien has run a follow-up study on children who experienced the program. (She tested the saliva and observed the behavior of 500 participants, ages 12-14 years.) The results of the study showed that the program successfully reduced stress hormones in children who were stressed.

“Not all children will respond because not all are suffering,” she explained. “The only factor that explains those who respond to the treatment is anger.” Children who started the school year angry became less angry after they took the program, she said, and their depression also decreased. “So, we are doing something good here.”

Addressing Stress in the Classroom Environment: CARE for Teachers

University of Virginia Professor of Education Patricia Jennings also addressed how stress impairs learning. Her concern, however, was how the stress teachers are under affects the classroom environment. Stress doesn’t only enter a classroom through the personal stories of the students, she explained. The classroom itself can become an incubator of emotions and reactivity. To create an environment conducive to learning, she said, teachers need help managing their stress too.

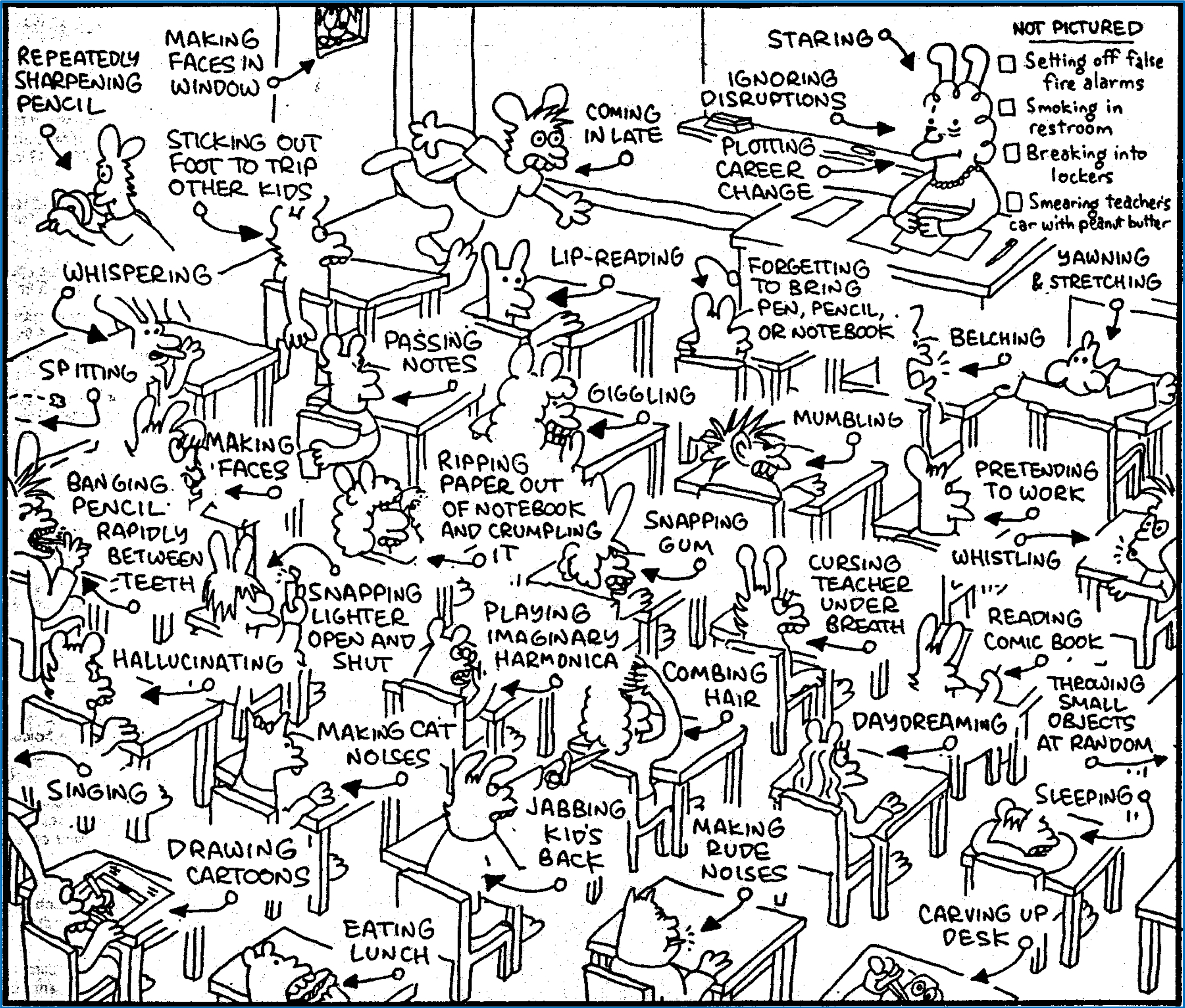

Jennings showed the Dalai Lama a cartoon portraying a classroom in chaos. “This is what it feels like sometimes when you’re teaching and the stress level of the teacher is going up,” she said. “It feels crazy!” She zoomed in on a corner of the image where one student was passing notes, another was whispering, and a third was ripping paper out of a notebook and crumpling it. The teacher has a lot to manage, she declared. “It is really challenging!”

Image provided by Patricia Jennings.

Teachers who experience levels of stress that overwhelm their coping ability can become emotionally and physically exhausted leading to burnout, Jennings said. They then get reactive, which alters their judgment, and they sometimes misinterpret what is going on. Jennings witnessed this when she was visiting classrooms. For example, on one occasion, “a student would do something that the teacher misinterpreted, and she would get mad at that student and punish that student. It would have a very negative effect on the student, and there was no reason for it.” In situations like this, students end up as the target, but the teachers’ anger really is caused by their own stress, Jennings said. “And when the teacher acts that way, the students get more disruptive,” so the stress escalates in the classroom, for everyone.

“I was watching this happen,” Jennings recounted, “and I thought, how can we help these schools?” Researchers knew that an emotionally supportive classroom environment predicts a better learning outcome, she recalled. They also knew such environments depends on healthy student-teacher relationships and that SEL programs can help. What they didn’t know, Jennings continued, “is what kinds of social and emotional competencies teachers need in order to do this.”

Jennings and her colleagues developed a 30-hour SEL training program to respond to the needs of teachers called Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education (CARE). “We call it ‘CARE for Teachers,’ which teachers really like, because they really need care and they appreciate it.” The program offers compassion practices, emotion skills training, and mindful awareness practices, she said. It helps teachers recognize when they are feeling stressed and understand how stress can alter their perception, so that they can realize, Jennings said, “Oh, maybe what I’m seeing is not true.”

At the start of the program, Jennings asks teachers to reflect about why they came into the profession. Many teachers come to teaching with a strong sense of compassion, she said. “We help them connect with that, and then we teach them how to set their intention so they can monitor their behavior in relationship to their intention.”

"A lot of teachers come to teaching with a strong sense of compassion. We help them connect with that, and then we teach them how to set their intention so they can monitor their behavior in relationship to their intention." Patricia Jennings

Jennings and her colleagues ran a large randomized control trial in high-poverty New York City schools to see if teachers who took the CARE program became more effective in the classroom. “It definitely improved teachers’ emotion regulation,” she said. Researchers also observed improvement in mindfulness and reductions in psychological distress. Importantly, for teachers in the CARE program, their classroom environments improved compared to those teachers not in the program. Not only were classroom climates found to be more positive and emotionally supportive, but participating teachers were more sensitive to student needs and students more productive and engaged. These outcomes were significant, Jennings said, because “this is the first time this measure has been shown to be affected by working only with the teacher.” (There was no change to the curriculum.)

Slide image © Patricia Jennings.

Targeting stress reduction in teachers is also important, Jennings stated, because teachers can lead by example. When they are starting to get stressed, teachers can demonstrate their own stress management for students to see. For instance, said Jennings, they can say aloud, “I am feeling stress. I notice tension in my shoulders, I’m going to take some breaths and calm down.” Children get to witness the process and observe the result: the teacher becomes calm, she said. “It is really a lesson in action.”

To find out more about the stress reduction programs and curricula described above, visit the Resources section. In Chapter 7 “Mindfulness and the Training of Awareness and Attention”, presenters examine another barrier to student success—mind-wandering—and how focused attention can help students avoid being overly distracted by their thoughts and emotions. Expectant and new mothers, too, can avoid depression through mindfulness practices involving attention and meta-awareness.